How to Meaningfully Measure On-Time Delivery of Anything

by Stacey Barr |On-time delivery is becoming ever more important in business. But the answer isn’t to deliver more quickly; it’s to deliver more predictably.

Believe it or not, but success in drag racing isn’t about speed. Sure, it’s a thrill to see (and feel) a top fuel dragster run an earth-shaking sub-four-second quarter mile. But the winner of any drag race, no matter the category, isn’t always the fastest car.

In drag racing, the winner is the most consistent. A friend of mine used to drag race her 1967 Warwick Yellow Holden HK GTS 327 Bathurst Monaro. It wasn’t the fastest car, but she would always do well because she was consistent:

- consistent reaction time

- consistent run time

- consistently close to her “dial in” time (and if you run faster than that, you’re disqualified – it’s a form of cheating, like setting a target that is way too easy)

Consistency means low variability. And low variability is the key to coming out on top. Donald Wheeler’s book title says it all: Understanding Variation – The Key to Managing Chaos.

Measuring on-time performance in business is no different to measuring drag racing performance.

On-time performance matters in almost every business or organisation. In their McKinsey article “Deliver On Time or Pay the Fine”, Kuntze et al explain that e-commerce players now more than ever compete on predictability and responsiveness in meeting their customer orders. They say “achieving on-time in-full delivery performance of 95 percent or more for even complex orders” is not about just going harder and faster. It’s about two basic things:

- how we use data to predict demand and the ability to meet it

- how well we can understand, streamline and automate our processes to reduce complexity and remove waste

But focusing on the traditional ways to measure on-time performance isn’t useful.

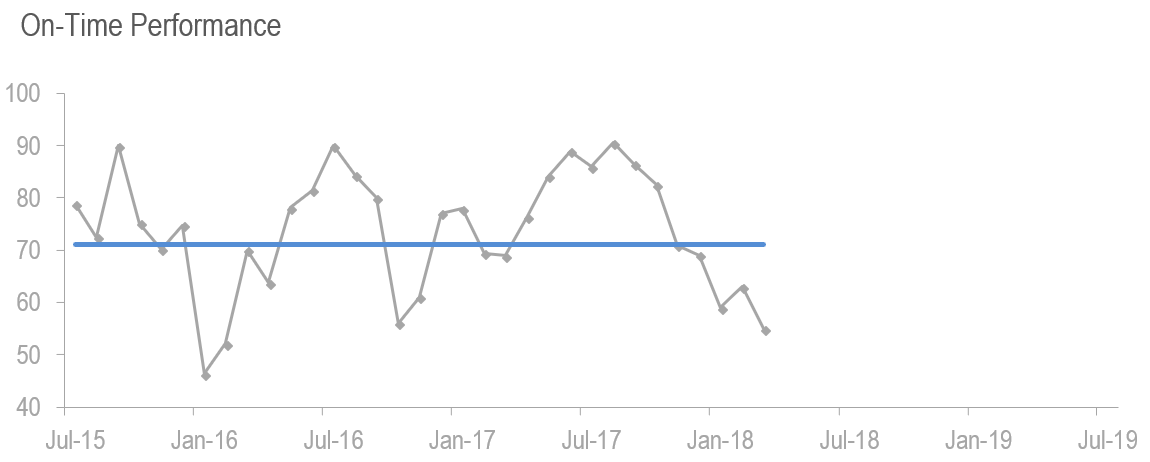

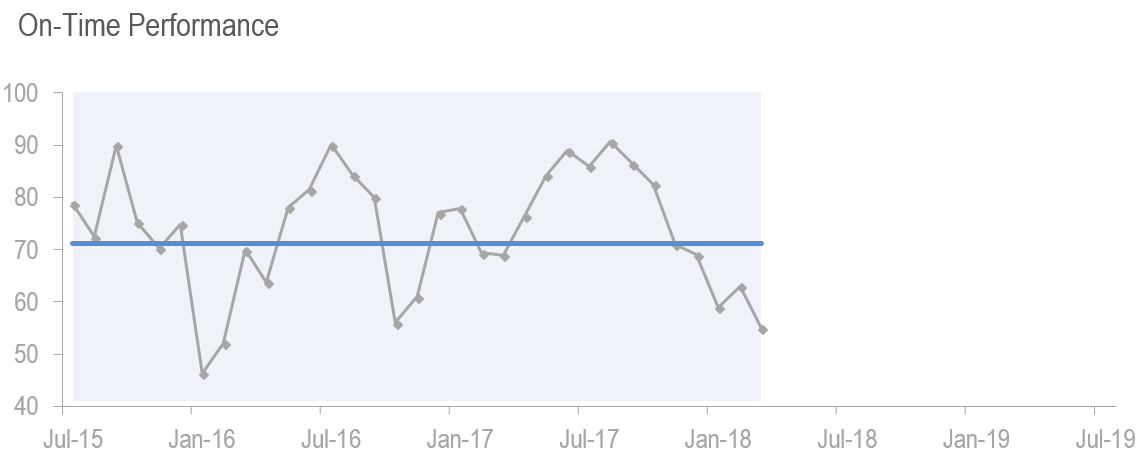

Measuring Percentage of Orders Delivered on Time, or Delivery On-Time and In-Full, or Delivery Cycle Time isn’t the solution. When we focus on averages, we naturally try to improve the average. But improvements are usually temporary, and not fundamental improvements.

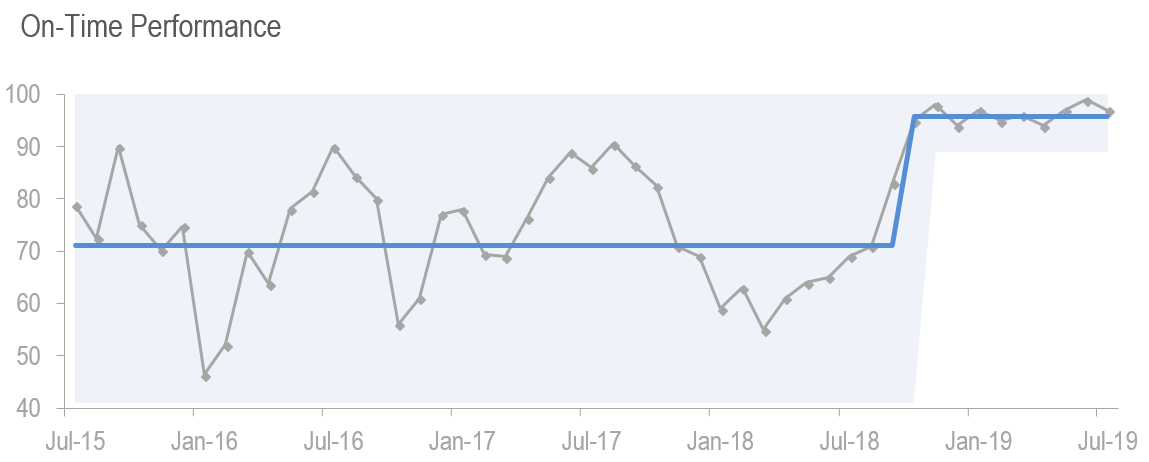

But improvement comes from reducing variation. To increase delivery speed, we first need to get more control over delivery. We need to make it more predictable. To do this, we need to measure variation and not just the average.

And

the consequence of becoming more predictable will be that it gets faster. That’s because by understanding the causes of variability in speed, we learn about where our process can be tightened up. We remove or reduce the impact of those causes of variability, and things get better.

Reducing variation in on-time performance matters in all aspects of business.

To survive, organisations can never stop caring about the on-time performance of customer orders, projects, new policies, technical solutions, and anything else they deliver. Our job is to understand the reasons why the on-time performance varies, and get more control over those reasons we can influence.

For example, delivery speed of customer orders will vary for all kinds of reasons. Many customers will have more complex orders, and we could use that as an excuse for slower delivery. But our job is to look for ways to more quickly handle that complexity. Amazon did this by expanding its network of fulfillment centres (and in some areas using drones to deliver smaller goods), to predictably deliver to their Prime customers within two days.

Another example is the on-time performance of projects. Project timelines can be a few weeks or a few months or longer, and we could use that as an excuse for treating each project as a special stand-alone performance challenge. But our job is to look for ways to remove idle time and rework from every project, to shrink the total time, no matter the project timeline. Peter Cook, in his book “The New Rules of Management“, talks about the discipline of scoping and completing 90-day projects, as a way to get more control over completion.

The essential action to take, to increase the speed of anything you deliver, is to understand the process that delivers it.

Absolutely measure the speed of what you deliver, but make sure you take a stoic approach to interpreting it, so you don’t make excuses for it or knee-jerk react to improve it.

Measure the variability in the speed each time you deliver that thing. And understand, streamline and automate what you can in the process, to keep removing variation. Then predictability will increase. And then more speed will be the natural consequence of higher predictability.

The key to improving on-time performance isn’t to measure speed; it’s to measure predictability.

[tweet this]

DISCUSSION:

In which areas of your business or organisation does on-time performance matter? Does the measure and its graph encourage you to focus on the average, or on the variation?

Connect with Stacey

Haven’t found what you’re looking for? Want more information? Fill out the form below and I’ll get in touch with you as soon as possible.

167 Eagle Street,

Brisbane Qld 4000,

Australia

ACN: 129953635

Director: Stacey Barr